Residents of Tillamook County, OR should have some serious empathy for those in the flood-ravaged Midwest. After all, we’ve had two record floods two years in a row. But there are some lessons to be learned from the case of Iowa as the following story from Joel Achenbach of the Washington Post (June 19 edition) points out. While the picture is—forgive the pun—muddy, the modification of the landscape in Iowa and the entire Midwest may be exacerbating the capacity of the region’s streams to hold, release and convey water during extreme rainfall events. H2ONC certainly agrees with that assessment and points to large-scale landscape modification in our own basins as reason to take heed of lessons from Iowa.

As the Cedar River rose higher and higher, and as he stacked sandbags along the levee protecting downtown Cedar Falls, Kamyar Enshayan, a college professor and City Council member, kept asking himself the same question: “What is going on?”

The river would eventually rise six feet higher than any flood on record. Farther downstream, in Cedar Rapids, the river would break the record by more than 11 feet.

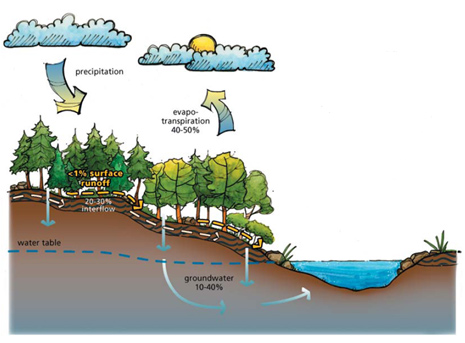

Enshayan, director of an environmental center at the University of Northern Iowa, suspects that this natural disaster wasn’t really all that natural. He points out that the heavy rains fell on a landscape radically reengineered by humans. Plowed fields have replaced tallgrass prairies. Fields have been meticulously drained with underground pipes. Streams and creeks have been straightened. Most of the wetlands are gone. Flood plains have been filled and developed.

“We’ve done numerous things to the landscape that took away these water-absorbing functions,” he said. “Agriculture must respect the limits of nature.”

Officials are still trying to understand all the factors that contributed to Iowa’s flooding, and not everyone has the same suspicions as Enshayan. For them, the cause was obvious: It rained buckets and buckets for days on end. They say the changes in land use were lesser factors in what was really just a case of meteorological bad luck.

But some Iowans who study the environment suspect that changes in the land, both recently and over the past century or so, have made Iowa’s terrain not only highly profitable but also highly vulnerable to flooding. They know it’s a hard case to prove, but they hope to get Iowans thinking about how to reduce the chances of a repeat calamity.

“I sense that the flooding is not the result of a 500-year event,” said Jerry DeWitt, director of the Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture at Iowa State University. “We’re farming closer to creeks, farming closer to rivers. Without adequate buffer strips, the water moves rapidly from the field directly to the surface water.”

Corn alone will cover more than a third of the state’s land surface this year. The ethanol boom that began two years ago encouraged still more cultivation.

Between 2007 and 2008, farmers took 106,000 acres of Iowa land out of the Conservation Reserve Program, which pays farmers to keep farmland uncultivated, according to Lyle Asell, a special assistant for agriculture and environment with the state’s Department of Natural Resources (DNR). That land, if left untouched, probably would have been covered with perennial grasses with deep roots that help absorb water.

The basic hydrology of Iowa has been changed since the coming of the plow. By the early 20th century, farmers had installed drainage pipes under the surface to lower the water table and keep water from pooling in what otherwise could be valuable farmland. More of this drainage “tiling” has been added in recent years. The direct effect is that water moves quickly from the farmland to the streams and rivers.

“We’ve lost 90 percent of our wetlands,” said Mary Skopec, who monitors water quality for the Iowa DNR.

Crop rotation may also play a subtle role in the flooding. Farmers who may have once grown a number of crops are now likely to stick to just corn and soybeans — annual plants that don’t put down deep roots.

Another potential factor: sediment. “We’re actually seeing rivers filling up with sediment, so the capacity of the rivers has changed,” Asell said. He said that in the 1980s and 1990s, Iowa led the nation in flood damage year after year.

This landscape wasn’t ready for the kind of deluge that hit Iowa in May and early June. Central and eastern portions of the state received 15 inches of rain. That came on top of previous rains that had left the soil saturated. Worse, the rain came at the tail end of an unusually cool spring. Farmers had delayed planting their crops. The deluge struck a nearly naked landscape of small plants and black dirt.

“With that volume of rain, you’re going to have flooding. There’s just no way around it,” said Donna Dubberke, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in the Quad Cities. “This is not just because someone put in a parking lot.”

The rising Mississippi River is expected to peak this week, threatening towns and farmland north of St. Louis as floodwaters continue to move down the river. So far, flooding and severe weather have killed at least 24 people in three states and injured 106, forced the evacuations of about 40,000, and driven corn prices to record highs.

Two levees burst just north of Quincy, Ill., yesterday morning, forcing the evacuation of the small town of Meyer. Yesterday afternoon, Illinois Gov. Rod Blagojevich (D) visited the town after viewing the nearby Sny Island Levee, about 12 miles downstream from Quincy and, at 54 miles long, the second-biggest levee on the Mississippi.

In Iowa, the National Weather Service has reported record flooding at 12 locations on four rivers, including the Cedar, the Iowa, the Wapsipinicon and the Mississippi. The U.S. Geological Survey has preliminary data showing 500-year floods on the Cedar, the Shell Rock, the Upper Iowa and the Nodaway.

The Great Flood of 2008 has, for many inhabitants of sandbagged Iowa, come awfully soon after the Great Flood of 1993. Or, as Elwynn Taylor, a meteorologist at Iowa State University, put it: “Why should we have two 500-year floods within 15 years?”

Taylor attributes the flooding in recent years to cyclical climate change: The entire Midwest, he says, has been in a wet cycle for the past 30 years.

There has also been speculation that global warming could be a factor.

“Something in the system has changed,” said Pete Kollasch, a remote-sensing analyst with the Iowa DNR. “The only thing I can point my finger at is global warming, but there’s no proof of that.”

Jeri Neal, a program leader for ecological systems and research at Iowa State’s Leopold Center, said all these things have a cumulative effect on the landscape: “It doesn’t have the resilience built into it that you need to withstand disturbances in the system.”

The idea of a 500-year flood can be confusing. Hydrologists use the term to indicate a flooding event that they believe has a 0.2 percent chance — 1 in 500 — of happening in any given year in a specific location. A 100-year flood has a 1 in 100 chance of happening, and so on. Such estimates are based on many years of data collection, in some cases going back a century or more.

But the database can be spotty. Robert Holmes, national flood coordinator with the U.S. Geological Survey, said a lack of funding since 1999 has forced his agency to discontinue hundreds of stream gauges across the country. “It’s not sexy to fund stream flow gauges,” he said.

What’s certain is that a lot of water had nowhere to go when the sky opened over Iowa this spring. Some rivers did things they’d never done before. The flood stage at Cedar Rapids, for example, is 12 feet. The previous record flood happened in 1929, when the Cedar hit 20 feet. This year the Cedar hit 20 feet and kept rising. Experts predicted it would crest at 22 feet, and then upped the estimate to 24 feet. The river had other ideas. At mid-morning last Friday, it finally crested at 31.3 feet.

The entire downtown was flooded and a railroad bridge collapsed, dumping rail cars filled with rock into the river.

“Cities routinely build in the flood plain,” Enshayan said. “That’s not an act of God; that’s an act of City Council.”

Staff writer Kari Lydersen contributed to this report from Quincy, Ill.